Learn more about muskrats in Illinois in OutdoorIllinois Journal:

Muskrats are an important part of the food web because they are a food source for many predators. For example, minks are particularly dependent upon muskrat populations. And muskrats serve as a sort of “developer” in the wildlife community—their abandoned burrows provide homes for several other species. Snakes, turtles, ducks, and wading birds use muskrat lodges and platforms to rest on. Additionally, as muskrats harvest plants, they create areas of open water that are used by waterfowl and wading birds.

Muskrats are large, aquatic rodents, 16 to 25 inches in length, including the tail. They weigh 1½ to 4 pounds. Their fur is typically dark brown, with the underside considerably lighter than the back.

Muskrats have small eyes and ears and short front legs with longer hind legs. They have five clawed toes on each foot, and the back feet are partially webbed. Muskrats are highly specialized for living in the water.

Muskrats are sometimes confused with beavers, but the two species are easy to tell apart by looking at the tail. Muskrats have thin, nearly hairless tails that are flattened vertically, while beavers have wide, broad tails that are flattened horizontally. Muskrats are also much smaller than beavers, which can weigh between 25 and 85 pounds.

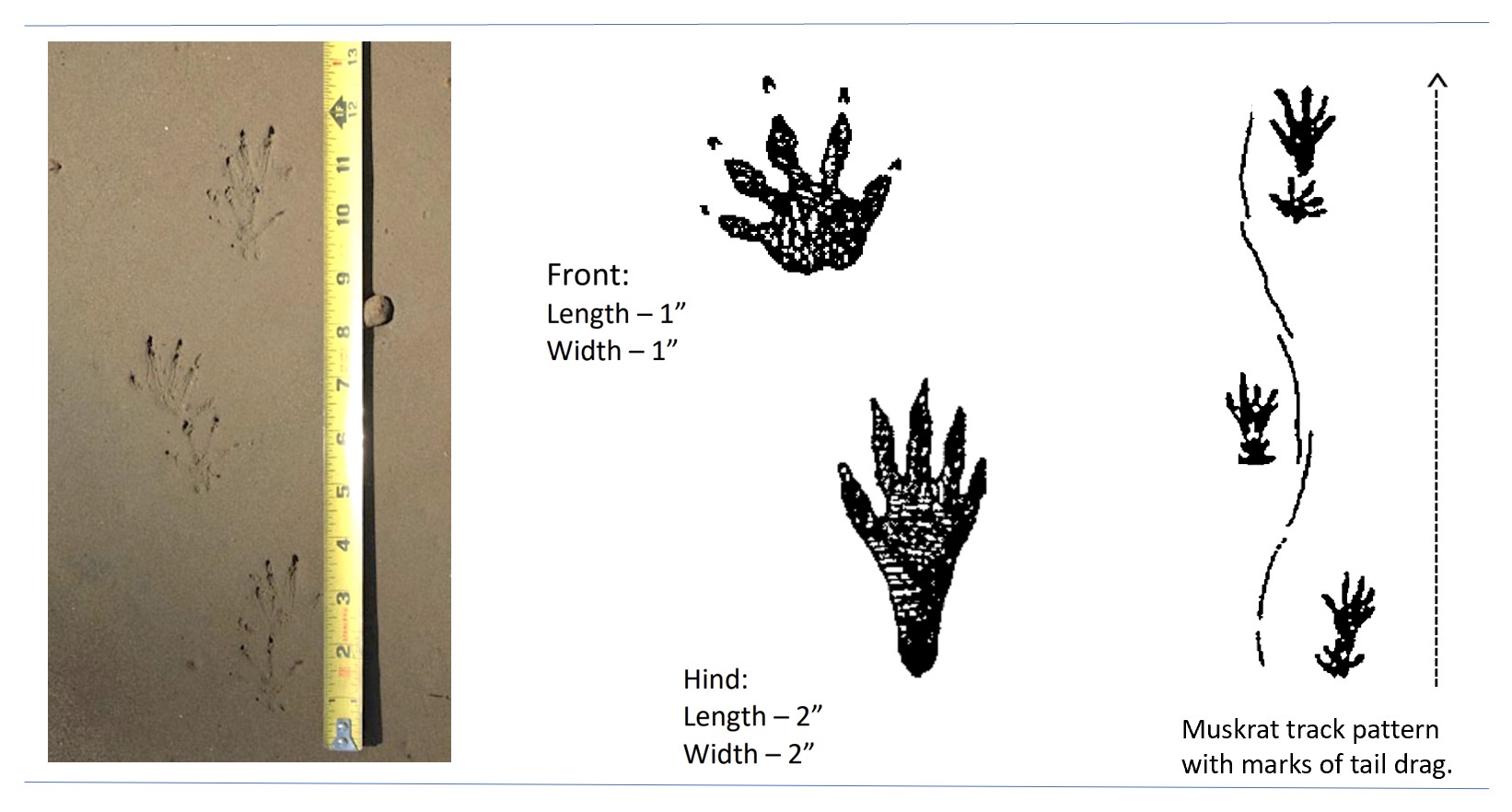

Muskrat tracks are found near water. Although they have five toes on the front feet, the inner toe is so small that it does not usually show up in a track. The tracks of the hind feet will be larger than those of the front feet. There may also be tail drag marks with the tracks.

Muskrats use latrine areas along the shoreline, typically a rock or log that projects into the water. They leave the water and deposit small, black to dark green, oval-shaped droppings on the latrine area.

Muskrats can be found in every county in Illinois, but are most abundant in the northern part of the state. While habitat loss due to drainage of Illinois wetlands caused a decline in the population, creation of ponds and drainage ditches has kept the muskrat fairly common throughout the state. Researchers have documented populations of more than eight muskrats per acre in marshes and 60 muskrats per mile of drainage ditch. Drought, flooding and harsh winters all affect muskrat populations, and their numbers can fluctuate drastically from year to year.

Biologists are conducting research and monitoring this species as some populations have declined and muskrats aren’t as common in some areas as they were historically. A recent study Assessing the Value of an Indicator Species for Wetland Quality, Connectivity, and Wildlife in the Great Lakes Basin found that in their study area in the Great Lakes Basin, county-level muskrat harvest was positively related to wetland connectivity and wetland area. The researchers suggest that declines in muskrat populations in recent decades may be related to wetland losses. They also found that drought conditions influenced harvest, such that per capita muskrat harvest during abnormally wet conditions was approximately twice that of abnormally dry conditions.

Muskrats are typically nocturnal (active at night) but may be seen during the day, especially on overcast days. They are also more active during the day in spring and early summer. Muskrats forage for food near their dens and tend not to travel far. Young are the exception, since they may have to travel fairly far to find their own territory. This search may take them over land, and during this time they are susceptible to being killed by vehicles or predators.

Muskrats typically live alone, although in fairly close proximity to one another. They may den together during the winter months. If food becomes a limiting factor, muskrats will become aggressive toward each other. Muskrats do not hibernate and typically do not store much food for the winter.

Muskrats are an important food source for many predators. Minks are particularly dependent upon muskrat populations. Additionally, abandoned muskrat burrows provide homes for several other species.

Muskrats can be carriers of tularemia, a disease caused by the bacterium Francisella tularensis. People can contract the disease by handling infected carcasses or consuming contaminated food or water. Symptoms typically appear three to five days after exposure and include fever, chills, headaches, muscle and joint pain, and diarrhea. The disease can be treated with antibiotics. This disease is not spread from person to person.

Muskrats are susceptible to other diseases and parasites, but these are not of concern to public health.

Muskrats inhabit aquatic areas of still or slow moving water. They can be found living in ponds, lakes, streams, swamps, marshes, stormwater management ponds and drainage ditches.

Those that live in swamps and marshes or other areas with a low water table often build lodges of aquatic, herbaceous vegetation. These lodges can be quite large measuring four to six feet in diameter. They will also construct smaller feeding houses or feeding platforms. Muskrats that live in deeper water often dig out burrows in the bank of ponds or drainage ditches. Muskrats enter both lodges and burrows through openings under the water. And they have several underwater trails to the lodge or den, which are called muskrat runs. Bank dwelling muskrats are more common than lodge builders in Illinois.

Muskrats breed from March to September, and most of the young are born between April and June. Gestation is 25 to 30 days. Females have two or three litters per year, producing an average of three to six young per litter. Females care for young on their own without the assistance of the male. Young are capable of swimming at three weeks of age and will be weaned by the time they are a month old. Females may have a new litter of young in a different nest chamber before the previous litter has dispersed to new habitat. If food is scarce, the older litter may eat the younger litter.

Muskrats have a short lifespan. It is estimated that two thirds of the young born each year do not make it through their first winter. Flooding is a major cause of mortality among young muskrats. Mink (Mustela vison) is the main muskrat predator, and they take both adult and young muskrats. Hawks, owls, coyotes, foxes, raccoons, large snakes and snapping turtles also prey upon muskrats. The oldest known wild muskrat in Illinois lived for four years.

Muskrats are most likely to cause problems by burrowing into pond and lake shorelines, dams and water control structures.

When constructing new ponds use the following specifications: The inside face of the dam should be built at a three-to-one slope and the outer face at a two-to-one slope. The top of the dam should be at least eight feet wide. The water level should be kept three feet or more below the top of the dam.

Stone riprap can be used to prevent muskrats from burrowing into pond dams. Bury chain link or welded wire fencing six to 12 inches below the soil surface and a minimum of several feet above and below the normal water level all along the shoreline or earthen structure.

There are currently no approved repellents for muskrats in Illinois.

Frightening devices are ineffective.

There are no approved toxicants or fumigants for muskrat control in Illinois.

Trapping is the most effective way of dealing with nuisance muskrats. A nuisance wildlife control operator can be hired if you wish to have someone remove the muskrats for you.

If you want to remove the animal(s) yourself, you will need a permit from an Illinois Department of Natural Resources district wildlife biologist before trapping muskrats. Your local district wildlife biologist can provide options for resolving problems, including issuance of a nuisance animal removal permit.

The IDNR Furbearers page provides more information about hunting and trapping Furbearers. The Illinois Trapper Education Manual provides guidance on the best management practices for trapping. Trap size recommendations for muskrats is found on page 90; see Trapper Education Manual.

Current hunting and trapping seasons can be found in the Illinois Digest of Hunting and Trapping Regulations or in the Legal Status section below.

Recreational fur-trapping is the preferred method to deal with nuisance furbearer issues. Trapping can help control the local population of animals and, in some cases, reduce the number of nuisance complaints and the damage that some species can cause. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources offers a lengthy trapping season (3 months, in some cases 4.5 months). Legal trapping can occur 100 yards from an occupied dwelling without permission of the occupants, closer with permission as long as there are no municipal ordinances that prohibit trapping.

Click HERE for more information from USDA-APHIS-Wildlife Services about dealing with damage caused by muskrats.

In Illinois, muskrats are protected as Furbearers. If a muskrat in an urban area is causing a problem, it may be trapped and removed if a nuisance animal removal permit is issued by an Illinois Department of Natural Resources district wildlife biologist. Current hunting and trapping seasons and regulations can be found in the Illinois Digest of Hunting and Trapping Regulations.

Photo: Stephen B. Hagar, Augustana College

Illustrator: Lynn Smith

Photo: Terry Kem and Illustrations: Dan Goodman

Photo: Bob Bluett

Photo: Stephen B. Hagar, Augustana College

The Wildlife Illinois website was authorized by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) in partial fulfillment of project W-147-T. The website was developed by the National Great Rivers Research and Education Center, 2wav, and the IDNR in partnership with the United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services and University of Illinois Extension to provide research-based information about how to coexist with Illinois wildlife.