Photo: Sheila Newenham

Learn more about river otters in Illinois in OutdoorIllinois Journal:

River otters are a top aquatic predator. Their presence in a waterway indicates a healthy ecosystem.

River otters are long, streamlined mammals. They can be distinguished from muskrats and beavers by their stout, tapered, furred tails. A broad, flattened head; prominent nose; long, bristly whiskers; small rounded ears; small eyes; and thick neck are other characteristics used to identify river otters. They are dark brown to nearly black with pale brown or gray undersides.

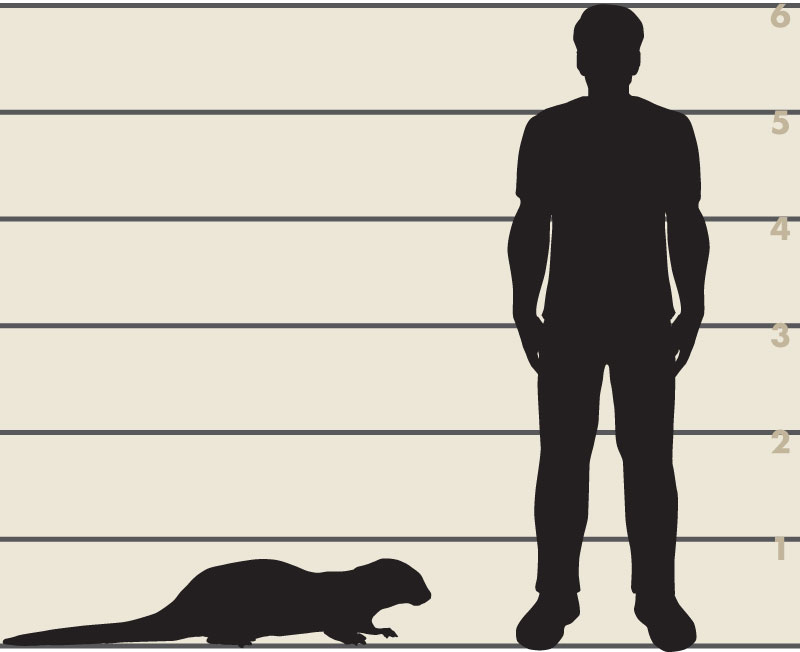

The legs of a river otter are short, with five webbed toes on each foot. They weigh 10 to 30 pounds and are 34 to 53 inches long from nose to the tip of the tail.

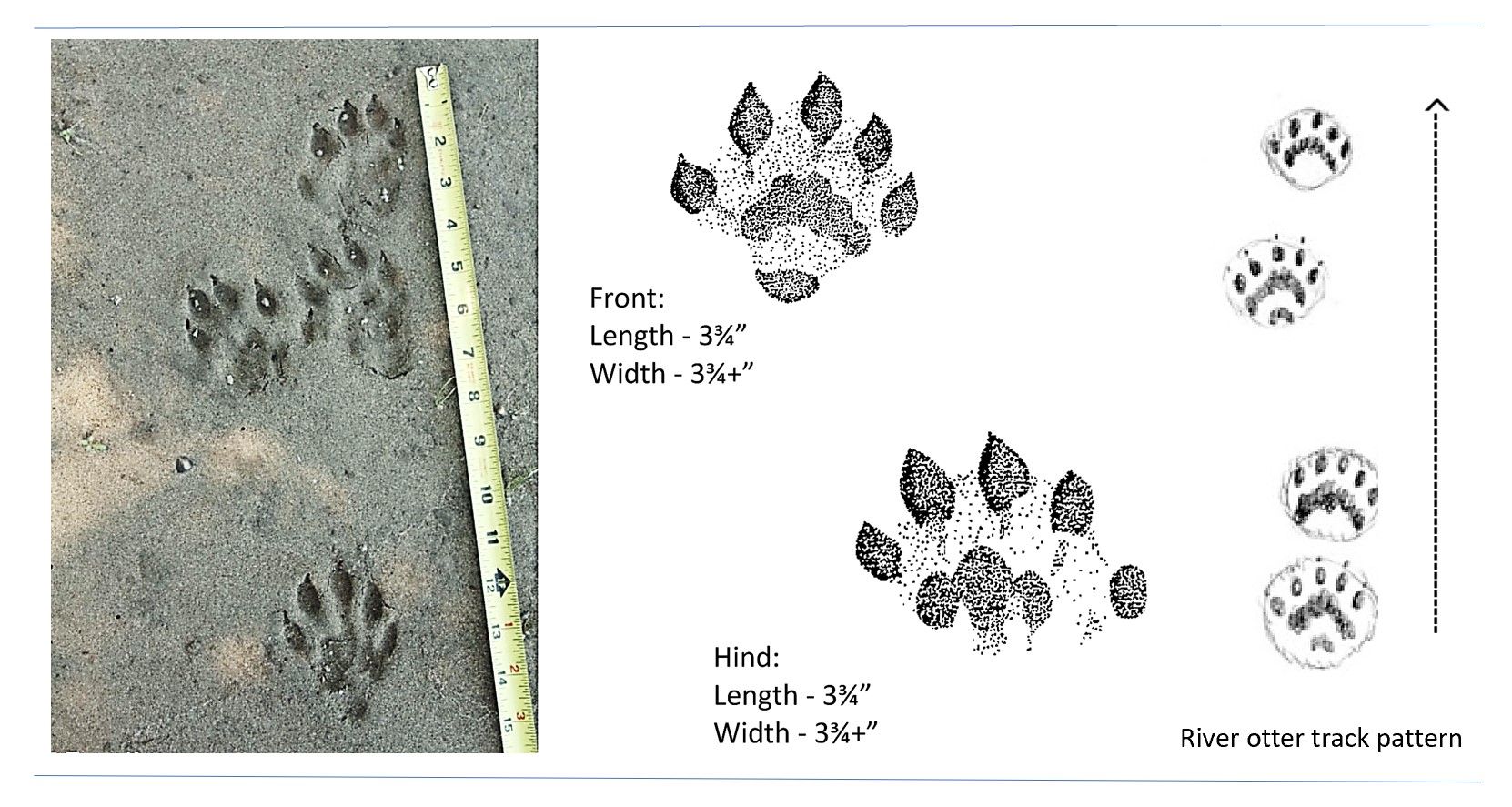

River otters have a loping gait when on land. Their tracks are approximately 2½ to 3½ inches wide, and the webbing and claw marks are often visible. On snow or ice, otters use a bound-and-slide form of locomotion. In snow, their tracks are interspersed with 10- to 20-foot slide marks.

River otters deposit their droppings (scat) in prominent locations near water, such as on a log or rock. One to many otters will use the same latrine area (known as spraints) many times. Fresh otter scat is dark and contains fish scales and bones or the remains of other food items.

At the time of European settlement, river otters were common throughout Illinois. Over the years, habitat loss, pollution, and unregulated hunting severely reduced the population. By 1989, biologists estimated that there were fewer than 100 river otters left in Illinois, and the river otter was added to the State Endangered Species list. In the mid-1990s, biologists with the Illinois Department of Natural Resources released 346 river otters from Louisiana in southeastern and central Illinois. River otter populations slowly increased. In 1999, river otters were upgraded to a State Threatened species. Further improvement in otter numbers allowed the river otter to be taken off the State Threatened list in 2004.

Today, the largest concentrations of river otters in Illinois are along the Mississippi River and its backwaters in northwestern Illinois. River otters are now a common species in Illinois and are found in every county. In some locations, river otter numbers have increased to such levels that the species is sometimes considered a nuisance.

River otters are crepuscular animals (active around dawn and dusk). Males are typically solitary but occasionally spend time with family groups or with small groups of males. Females are usually accompanied by their young.

River otters are exceptional swimmers. Their body shape and broad tail help them to maneuver quickly in the water. They are capable of submerging for three to four minutes at a time and can swim a quarter of a mile underwater. River otters are very curious, playful animals. They are known to play with rocks and shells and to slide down steep banks. Occasionally, a curious river otter will approach a boat or a person standing motionless on the shore, in order to investigate the new object in their territory.

River otters are not considered a public health concern in Illinois.

River otters can be found in rivers, streams, and lakes. Habitats with nearby timber and wetlands are preferred. Otters do not dig their own burrows and will often take over abandoned beaver dens. In areas without beaver dens, river otters will use abandoned muskrat or woodchuck burrows.

Over the course of a year, a male river otter may use 40 to 100 linear miles of shoreline. Seasonally, a female river otter and her young will use relatively small sections of a waterway, typically 3 to 10 linear miles. Females tend to have smaller home ranges than males.

River otters feed mainly on fish and crayfish but will also consume frogs, salamanders, snakes, small turtles, aquatic invertebrates, earthworms, and carrion. They will pull large fish from the water so that they can feed on land, and they often leave uneaten fish parts on the shoreline. These signs can be used to help determine the presence of river otters in an area.

River otters breed in late winter to early spring (January to April). The female carries the fertilized eggs for 8 to 12 months before embryo development occurs (delayed implantation). Two to four kits are born two months later, arriving between January and May.

The female raises the kits, mostly without male assistance. Kits begin brief trips outside the den when they are 10 to 12 weeks old and take to the water when they reach approximately 14 weeks. Young river otters must be taught to swim and are weaned by four months of age, but they often remain with the female until the following spring.

Bobcats and coyotes are the main predators of river otters. Adults are able to defend themselves against most predators. If they survive the first year, river otters often live for 8 to 10 years.

River otters are not likely to cause problems in natural environments. Exclusion and removal are the best methods to remedy a fish depredation problem with river otters.

River otters do not build their own dens. Modifying the landscape by destroying beaver and muskrat lodges and burrows may discourage river otters from taking up residence on the property.

If otters are already present, adding aquatic vegetation or brush piles to ponds can provide fish with cover to help them escape river otters.

Fencing is an effective, but often expensive, technique to keep river otters out of an area. Water tanks or small ponds can be fenced with 3 x 3-inch mesh wire. High-tensile electric fences can also be effective. Four strands of wire should be placed at 4 to 5-inch intervals from the ground. Wires must be spaced closely enough that the otter cannot go underneath or between the wires without receiving a shock. Remove vegetation around the fence to prevent the electric charge from becoming grounded.

There are no repellents registered for use to deter river otters in Illinois.

River otters may be trapped by licensed sportsmen or sportswomen with a valid permit issued by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Landowners experiencing property damage outside of the trapping season can contact a district wildlife biologist for advice on mitigating damage, which could include adding structures to ponds to provide refuge for fish to make catching fish more difficult for otters, or to request a nuisance animal removal permit. An experienced nuisance wildlife control operator may also be hired remove river otters.

The IDNR River Otter Trapping page provides more information about trapping river otters. The Illinois Trapper Education Manual provides guidance on the best management practices for trapping, and trap size recommendations for river otters can be found on page 90: Trapper Education Manual.

River otters may be legally be trapped mid-November through March. Current trapping season dates and regulations can be found in the Illinois Digest of Hunting and Trapping Regulations. Follow all trapping regulations. The limit is 5 otter per trapper and a CITES pelt permit must be purchased ($5) within 48 hours of capture.

Recreational fur-trapping is the preferred method to deal with nuisance river otter issues. Trapping can help control the local population of animals and, in some cases, reduce the number of nuisance complaints and the damage that some species can cause. The Illinois Department of Natural Resources offers a lengthy trapping season (3 months, in some cases 4.5 months). Legal trapping can occur 100 yards from an occupied dwelling without permission of the occupants, closer with permission as long as there are no municipal ordinances that prohibit trapping.

River otters are legally protected by the Illinois Wildlife Code as Furbearers. If a river otter is causing property damage or is a public safety concern, it may be removed if an Illinois Department of Natural Resources district wildlife biologist issues a nuisance animal removal permit. They may also be trapped by an experienced nuisance wildlife control operator. They may also be taken during the legal season; current trapping season dates and regulations can be found in the Illinois Digest of Hunting and Trapping Regulations.

Photo: Tim Daniel, Ohio DNR, IDNR image library

Illustrator: Lynn Smith

Photo: Terry Kem and Illustrations: Dan Goodman

Photo: Glenn Chambers, IDNR image library

The Wildlife Illinois website was authorized by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) in partial fulfillment of project W-147-T. The website was developed by the National Great Rivers Research and Education Center, 2wav, and the IDNR in partnership with the United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Wildlife Services and University of Illinois Extension to provide research-based information about how to coexist with Illinois wildlife.